Catching Up with CALS — May 17, 2023

Dean's Message — Sugar, Candy and CALS

Made with caramel-flavored marshmallow, milk chocolate and sea salt, a Vandal bar always makes a great treat for $1.99. All profits from the Idaho Candy Co.’s University of Idaho-themed, letter “I”-shaped confection, released in November 2022, go toward scholarships benefiting our students. The candy bar’s black-and-gold wrapper — featuring the likeness of U of I mascot Joe Vandal and the words, “Partially made with genetic engineering (GMO)” — references a fruitful collaboration involving a local food manufacturer, sugar beet farmers and U of I. Idaho sugar beets are raised from GMO seeds developed to resist glyphosate herbicide, thereby reducing farmers’ chemical and labor costs and helping them operate more sustainably. Processing removes all traces of GMO DNA from the finished product, which is why beet sugar was exempted from a recent federal law requiring the labeling of foods containing a GMO ingredient. Still, some confectioners have switched to “conventional” sugar cane, concerned they could face consumer pushback based on public misperceptions regarding the technology. Idaho Candy, by contrast, stuck by Gem State sugar beet farmers and wants the public to know it, choosing to voluntarily acknowledge its use of beet sugar on product labels despite the federal exemption. Amalgamated Sugar, which processes sugar beets from more than 700 growers in its cooperative, has been Idaho Candy’s supplier since 1901. “We’ve always bought their sugar,” said U of I alum Dave Wagers, ’88, who heads Idaho Candy. “Our job is to buy Idaho and support Idaho stuff because really that’s why people support our products — to buy Idaho.”

Half of all sugar produced in the U.S. comes from sugar beets, and Idaho ranks as the nation’s No. 2 sugar beet-producing state. Helping to change the narrative about sugar beets, Matt Fisher, UI Extension area educator based in Twin Falls, is developing a sugar beet curriculum for University of Idaho Extension 4-H Youth Development program. Addressing challenges facing sugar beet farmers has also been a top CALS priority. We’ll soon help farmers who raise sugar beets and the state’s other staple crops make their farms even more sustainable through “Climate-Smart Commodities for Idaho: A Public, Private, Tribal Partnership.” The CALS-led project is funded with a five-year grant for up to $55 million — the largest award in the university’s history — and will offer financial incentives to Idaho producers who try practices intended to improve soil health and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Additional evidence of our college’s strong commitment to the sugar beet industry can be found in the pages of the recently published annual research edition of Amalgamated Sugar’s magazine, “The Sugarbeet.” The table of contents lists a dozen articles submitted by CALS scientists highlighting the work we did with the crop throughout 2022. One project concluded there could be benefits associated with delaying fungicide applications for controlling a devastating disease affecting sugar beets, powdery mildew. The researcher also found irrigation method can significantly influence powdery mildew severity. Another article described how the Pacific Northwest Pest Alert Network, which faculty from U of I and Oregon State University Extension established in 2002, has provided money-saving updates on pest outbreaks to its 2,200 subscribers. In a survey, subscribers reported using 5.56% less pesticides. The savings incurred by reducing just one pesticide application is significant — the cost of the chemical as well as the labor and equipment involved in the application add up quickly. CALS helped Amalgamated Sugar create a new tool for in-field soil health assessments. CALS entomologists surveyed strains of beet curly top virus and characterized species and population sizes of leafhoppers, which vector the disease. This helped them determine when beet fields are most at risk to curly top exposure. Our entomologists also studied how to use pheromones and colors to attract, trap and kill sugar beet root maggot flies. Our weed scientists have surveyed glyphosate resistance in kochia (a noxious invasive weed) throughout the state, and they’ve researched the effects of herbicide carryover on sugar beet yields, as well as practices to reduce the risk of carryover.

The sugar industry also invests heavily in CALS. Farmers pay assessments on the sale of specific commodities, including sugar, and apply the revenue toward marketing and research. Much of those assessment dollars are invested in our research projects, as well as in hiring technicians who aid our faculty. We sometimes leverage funding from commodity groups to land large, federal grants, addressing nationwide challenges, often in collaboration with researchers from many other institutions. To ensure our scientists take on the most pressing production challenges, U of I and the sugar beet industry have started discussions about improving how we submit research proposals. Amalgamated Sugar always has a presence at our career fairs and has a track record of hiring graduates from CALS and other U of I colleges. The company also provided real-world experience for CALS Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology Department undergraduates, providing them funding to develop 2022 Sugar Beet Enterprise Budgets, which help guide farmers’ decisions. Amalgamated Sugar further demonstrated its commitment to keeping the CALS research pipeline flowing by donating $500,000 toward forthcoming improvements at the U of I Parma Research and Extension Center. “Amalgamated Sugar and the University of Idaho CALS have a long history of cooperation related to the Parma research station,” Amalgamated Sugar President and CEO John McCreedy said. “When asked to invest in the new Parma facility, Amalgamated Sugar’s leadership and Board of Directors did not hesitate to invest in the facility because of high-quality functional agricultural research that will serve our growers, the sugar beet industry at large and other crop needs. This research will be critical to our future and the future of agriculture in Idaho.”

Michael P. Parrella

Dean

College of Agricultural and Life Sciences

By the Numbers

The 2022-2023 Heritage Orchard Conference Webinar Series, organized by University of Idaho’s Sandpoint Organic Agriculture Center, reached more than 550 apple enthusiasts in 45 U.S. states, 6 Canadian provinces and 13 countries throughout the world. The center includes a certified organic heirloom fruit orchard which produces 68 varieties of apples, 8 varieties of pears and 8 types of other fruits.

Our Stories

Malaria, Vector-borne Disease Grants

Researchers from University of Idaho (U of I) and University of Arizona (U of A) have received a four-year, $2.7 million grant through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to further their prior research on how to block transmission of the malaria parasite by mosquitoes.

In the realm of training, the U of I Institute for Health in the Human Ecosystem (IHHE) also recently received a separate five-year, $250,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Division of Experimental Biology, Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases (NSF DEB EEID) to support scholarships for their annual six-day course on the biology of vector-borne diseases.

The new NIH research grant was awarded to Shirley Luckhart, a professor in U of I’s Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology and Nematology and the Department of Biological Sciences, and Mike Riehle, an entomology professor with U of A, for their work on a biochemical pathway in mosquitoes that could lead to the development of an important new tool in the global effort to control malaria.

Luckhart and Riehle have collaborated for more than 18 years, seeking to understand the biochemical mechanisms of mosquito resistance to infection by malaria parasites, which are single-cell protozoa. April 25 is World Malaria Day, recognizing the importance of combating a disease that claimed 619,000 lives in 2021, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), with 95% of all malaria cases in the WHO African Region.

Luckhart and Riehle and their research teams previously created a genetically modified strain of mosquito that resisted malaria parasite development. Their screening of this genetically modified mosquito pinpointed an over-activated biochemical pathway that proved to be the mediator of resistance to the malaria parasite.

Based on their analysis of the pathway, they identified drugs developed by St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital for treatment of a rare genetic condition, which when administered orally to mosquitoes depletes their pool of an essential nutrient, vitamin B5. The drug activates the conversion of vitamin B5 in mosquitoes into another compound, coenzyme A, thereby starving the malaria parasite.

Luckhart envisions administering the medication to mosquitoes via bait stations in regions where malaria is prevalent. The bait stations would be part of a multipronged approach also involving insecticidal treatments and use of recently developed malaria vaccines, which confer between 30-40% and perhaps up to 75% protection. Mosquitoes have already developed resistance to many insecticides so having other tools available to combat the disease is critical.

“This type of strategy can complement other existing approaches — new drugs, new insecticides, new vaccines, etc. — to eliminate and ultimately eradicate malaria,” Luckhart said.

The new NSF DEB EEID training grant was awarded to Luckhart and Edwin Lewis, who is also a professor in U of I’s Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology and Nematology. Luckhart and Lewis are co-directors of the U of I IHHE, a campuswide institute that supports research, training and mentoring in the complex factors from the cellular to the ecosystem scale that impact plant, animal and human health.

Their six-day course is taught each June at the Moscow campus to train graduate students, faculty, health practitioners, government workers and policymakers to “concurrently and holistically address plant, animal and human vector-borne diseases as interconnected health challenges.”

More than 200 interested trainees from throughout the world have already applied for 40-50 open spots available for this year’s course.

“Despite growing recognition that these diseases are connected across biological and ecological scales, we face substantial intellectual and logistical obstacles in effecting these changes,” Lewis said. “Viruses that infect plants are not all that different from those that infect humans, but the scientific communities that work on these pathogens seldom, if ever, interact.”

The grant will support 10 international trainees and four domestic trainees per year. The support covers the $2,000 course fee, which includes housing, meals and course materials. There is additional support for travel, with $2,000 available for international trainees and $500 available for domestic trainees.

The project “How to Starve a Parasite: Manipulating CoA Biosynthesis to Control Plasmodium Development in the Mosquito” was funded with a four-year, $2.7 million grant under award No. R01 AI170506.

The training course “University of Idaho Institute for Health in the Human Ecosystem Biology of Vector-borne Diseases Course” was funded with a five-year, $250,000 grant under award No. DEB-2316443.

A Century of Weather Records

At 8 a.m. sharp every day of the year, staff at University of Idaho’s Aberdeen Research and Extension Center conduct a 30-minute chore that has been done unfailingly for more than 110 years.

Though the National Weather Service’s (NWS) fully automated weather station stands just a stone’s throw away, about a dozen Aberdeen crew members take turns manually recording meteorological readings from simple instruments housed within a small, fenced enclosure adjacent to their research fields.

Their morning ritual traces back to 1912 — the second year of operations at the Aberdeen research facility — and the handwritten logbooks they have produced throughout the decades represent one of Idaho’s lengthiest and most complete meteorological archives. They report the numbers monthly to NWS’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“It is public data used all over,” said Chad Jackson, operations manager in Aberdeen. “Some people ask, ‘Why in the world are you taking manual weather data when you have an automated weather station next to this?’ This is complete data, it’s always been done this way and it’s a continuous dataset. It takes a human eye to do some of these things.”

At the historic weather station, staff record the ambient temperature, soil temperature, precipitation, windspeed and snow-water equivalent. They use a tub of water to record water temperature and the rate of evaporation, providing a valuable tool to area water managers to help gage summer evaporative losses from nearby water bodies, such as American Falls Reservoir. They also jot down daily observations on cloud cover and winter observations on snow depth. Records from 1912 through 2010 specify the date of each season’s first killing frost — typically in mid-September. The information helped data users estimate the average growing season length.

The maximum precipitation recorded in a single day at the station was in 1952, when 2.41 inches of rain fell. The high temperature at the station was 104 degrees, reached in 1931, 1934 and 2006. The station’s maximum single-day snowfall occurred on Jan. 24, 2017 — 13 inches. The coldest temperature recorded was negative 42 degrees in 1922. The average annual precipitation at the station throughout the past century is 8.7 inches.

Land-grant universities such as U of I operate some of the longest-running weather stations in the country. U of I also operates a weather station dating back to the college’s early days in Moscow.

Records from the old Aberdeen facility are still routinely put to several important uses. The federal Bureau of Reclamation, for example, uses the data in its modeling, NWS uses it for climate forecasting and UI Extension includes it in a small grains report. U of I researchers also use the data for research.

“I personally have used it for determining weather trends and precipitation over historical amounts,” Jackson said.

One such research project involved using the data to correlate La Nina weather patterns with precipitation and disease levels. Jackson found that neither precipitation nor disease were strongly correlated with La Nina winters in Aberdeen.

Following an extremely wet August of 2014, during which grain farmers coped with widespread sprout damage, Jackson used weather station data on the number of wet days historically during that month to determine if it would be in the university’s best interests to start breeding grain varieties for sprout resistance.

“Basically, I figured out that it was once in 2,500 years that they have that much rainfall for that long of a duration in August. It was a real anomaly,” Jackson said, explaining breeding sprout-resistant grain varieties is unnecessary, if weather patterns remain consistent.

Recordings from the manual weather station are usually extremely close to the NWS automated station’s readings, which are updated every five minutes.

Idaho CAFE Construction

Excavation crews have started laying the groundwork on local farmland for the University of Idaho-led Idaho Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment (Idaho CAFE), which will include the nation’s largest research dairy.

Earthmoving began on May 4. Once the site is prepared, construction workers will begin pouring cement for the milking parlor. The first cows may arrive at Idaho CAFE before the end of 2024, with milking starting in early 2025.

U of I and its partners had hoped to start work last summer but have reaped rewards from their choice to delay building Idaho CAFE, allowing time for exorbitant construction costs to fall. The price of building the project’s initial phase, which will include a 2,000-cow dairy adjacent to a 640-acre research farm, dropped by roughly $4 million during the hiatus following a ceremonial groundbreaking for the project on June 30, 2022.

“The outlook is very bright,” said Mark McGuire, director of the Idaho Agricultural Experiment Station. “The lower bids mean we have sufficient funds to fully build this project.”

The general contractor, McAlvain Construction of Boise, suggested pausing the start of work and rebidding the subcontracts during winter, banking that labor and material costs would drop and that a more competitive field of bidders would emerge. The strategy worked, as bids from subcontractors for a greater scope of work recently came back significantly below last summer’s numbers.

Fuel prices were high and excavation companies were involved in many jobs last summer. U of I received a single bid for the excavation work. By contrast, several excavation companies competed for the recent bid. Supply chain constraints have also relaxed, leading to more affordable materials such as concrete.

“This has been such a long time coming and the excitement last year at the groundbreaking was just overwhelming how many people showed up,” said Tammie Newman, director of preconstruction with McAlvain. “It was probably the biggest attended groundbreaking I’d ever been to. Now the dream is a reality. When they sent me the picture of all of the equipment on site ready to start moving dirt, I was so excited.”

Faces and Places

Hannah Kindelspire, a dietetics graduate student from Moscow, and Jackie Davis, a dietetics graduate student from Lewiston, recently attended the Idaho Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Conference in Boise where they engaged with dietitians and nutrition professionals from the state of Idaho and dietetics students from other academic institutions. The trip was funded in part by generous donations from alumni and friends to the CALS Dean’s Excellence Fund.

CALS students Ariana Olmos, Brianna Leon, Krystal Conley Natividad, Michelle Saldana, Alejandro Jimenez and Narcisse Mubibya, and Student Services Manager Sharon Murdock recently attended the Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources and Related Sciences (MANRRS) national conference in Atlanta.

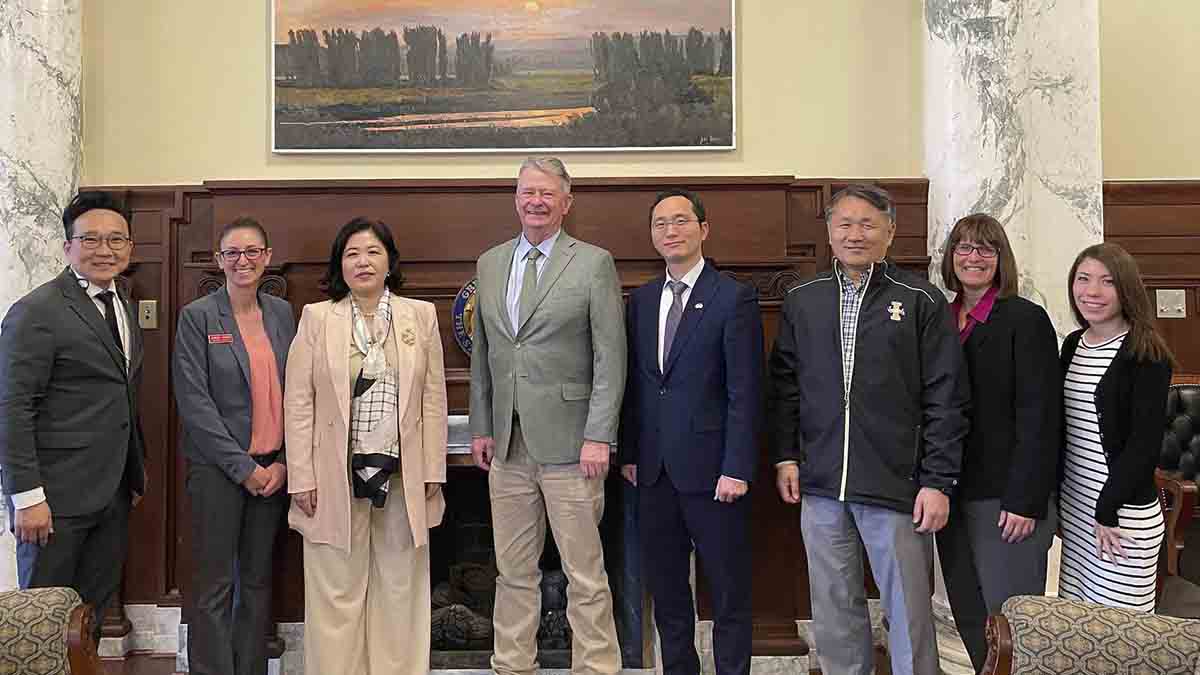

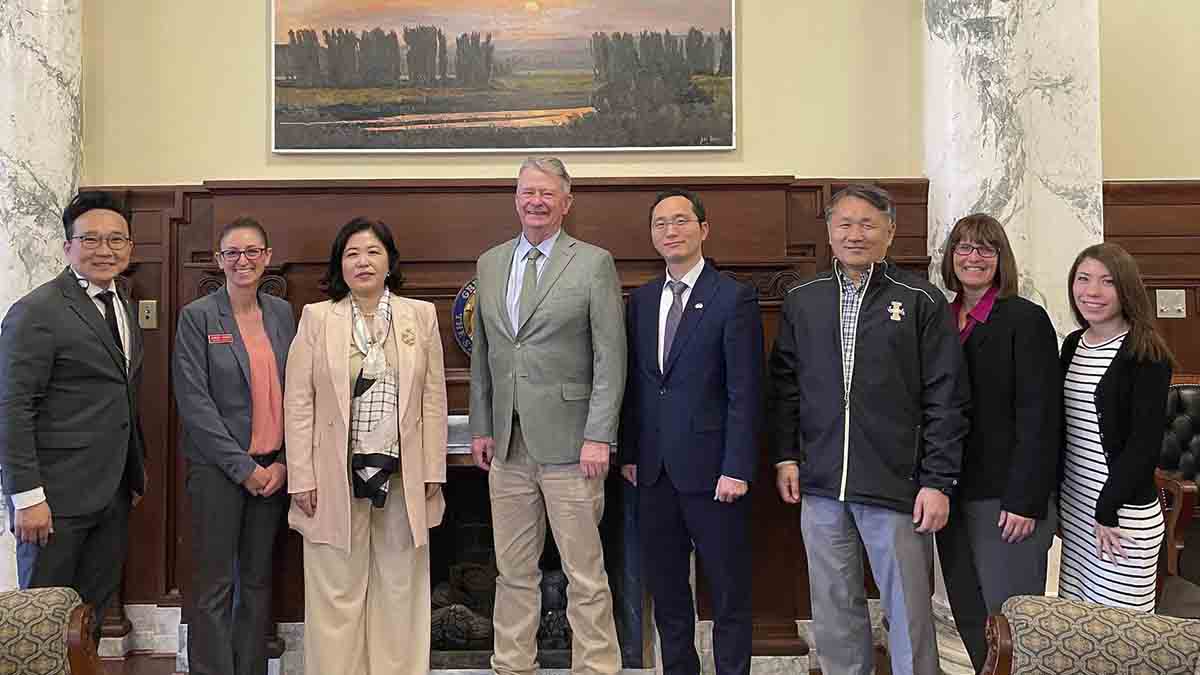

Associate Professor Jae Ryu recently facilitated a visit by Republic of Korea Consul General Eun-ji Seo to Boise for a series of events related to commemorating 70 years of U.S./ROK alliance. Ryu is the president of the Idaho Korean Association.

Events

- June 2, 3 — Sagebrush Saturday, Lecture on recreation in Hailey, June 2; Hands-on activity at Rinker Rock Creek Ranch, June 3

- June 6 — Ag Talk Tuesday, online

- June 6-9 — Idaho FFA Career Development Events, Moscow

- June 14, 21, 28 — Forestry Shortcourse, U of I Sandpoint Organic Agriculture Center

- June 26-29 — Idaho 4-H State Teen Association Convention, Moscow