Nocturnal Exploration

U of I’s Bat Girls Use Echolocation to Gather Info on Idaho Bat Species

Klara McKay’s introduction to bats was eventful — if brief.

One of the nocturnal flying mammals landed on a fellow camper during a youth outing in Montana. After a moment of distress, the excitement waned, and the bat was released into the night.

A few years later, McKay, who grew up in Missoula, took a field trip to the Lewis and Clark caverns where a ranger’s passionate narration regarding the cave’s bat population excited the then-teenager.

I’m really drawn to bats now. Elyce Gosselin, doctoral student

“Our guide told us about the research being done on the bats in the caves and hearing the guide talk about the bats with such enthusiasm is one of the reasons I was inspired to study wildlife,” McKay said. “I even thought, in that moment, that it would be cool to study bats, but I didn’t think it would really happen someday.”

McKay, a senior majoring in ecology and conservation biology, is one of the University of Idaho’s “bat girls,” a dynamic duo charged with gathering missing information about Idaho’s 14 bat species. She works with doctoral student Elyce Gosselin, the other half of the duo, as they use the bats’ echolocation to tease out the details of North Idaho’s bat populations — including preferences in habitat and peaks in activity levels — by recording the high frequency sounds the nighttime hunters emit.

Echolocation, ultrasonic pulses that bounce off nearby surfaces and return to the bat, allows bats to sense their surroundings. The sounds — most of which are too high in frequency for humans to hear, but bats can detect them — are used to forage, navigate and communicate. The reflected sounds provide bats with data to determine the orientation, size and distance of surrounding objects, including delectable insects.

Gosselin, whose bat studies have taken her to Ecuador and the Galapagos, is earning a doctorate doing what she likes best: Getting outside in the dark to study the world’s only flying mammal.

“It’s a different kind of adventure,” Gosselin said. “I like being out at night in the forest catching these strange little animals.”

Because of the challenges of identifying bats at night by sight or sound, the two researchers record the animal’s echolocation to log and catalogue local bats.

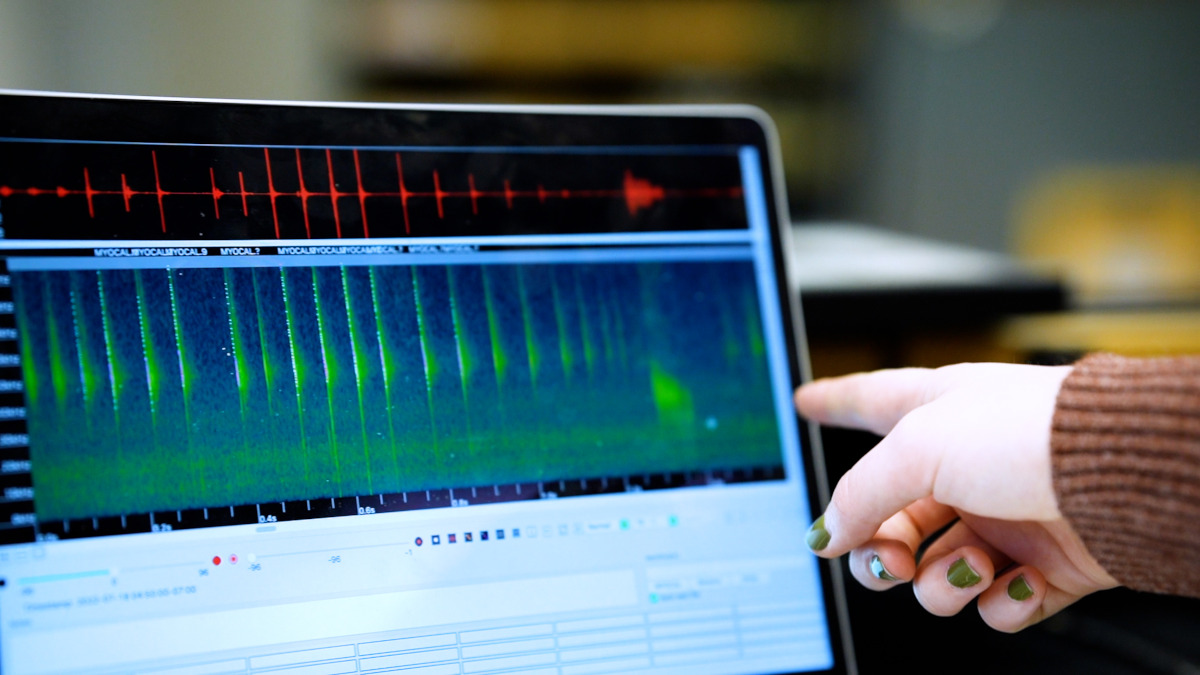

Gosselin and McKay set up echolocation monitoring stations at more than a dozen locations in the U of I Experimental Forest, periodically downloading the data, which on paper looks like an electrocardiogram. Much of the duo’s research involves determining which bat species are making the sounds.

“We usually view the calls using a specialized program that helps us identify the calls to species,” Gosselin said.

From that data, the researchers can determine foraging behavior and nightly peaks in activity levels between different species.

“Acoustic monitoring is an emerging non-invasive technique that can be used to study bats,” McKay said. “Because many species of bats have unique calls, recordings of bat calls can identify the species on a spectrogram using diagnostic features such as frequency and shape of the echolocation patterns.”

So far, the women have recorded 5,155 bat calls, detected 13 distinct species in the Experimental Forest east of Moscow and have identified 40% of the recordings.

Future analysis of the data will help create models which test how meteorological variables, habitat types, time of night and reproductive seasons influence bat activity levels, McKay said.

McKay’s background in undergraduate research at U of I includes radio collaring white-tailed deer fawns and performing deer necropsies. On another project, she catalogued images of animals captured on Idaho Fish and Game field cameras.

“After that summer of fieldwork, I knew I wanted to pursue wildlife research as a career,” she said.

Gosselin’s research has taken her to Mozambique to study antelope and elephants, but proficiency in Spanish led her to a South American bat study.

After several years of collecting information on bats she is locked in on the mysterious, furry fliers.

“At first I knew nothing about bats,” Gosselin said. “It was a steep learning curve, but I am invested. I’m really drawn to bats now.”

Article by Ralph Bartholdt, University Communications and Marketing.

Photos by Melissa Hartley, Visual Productions.

Published in February 2023.