A Musical Take on the Silent Screen

School of Music student’s original score for “The Phantom of the Opera” heads to the silver screen

It started out as a dare.

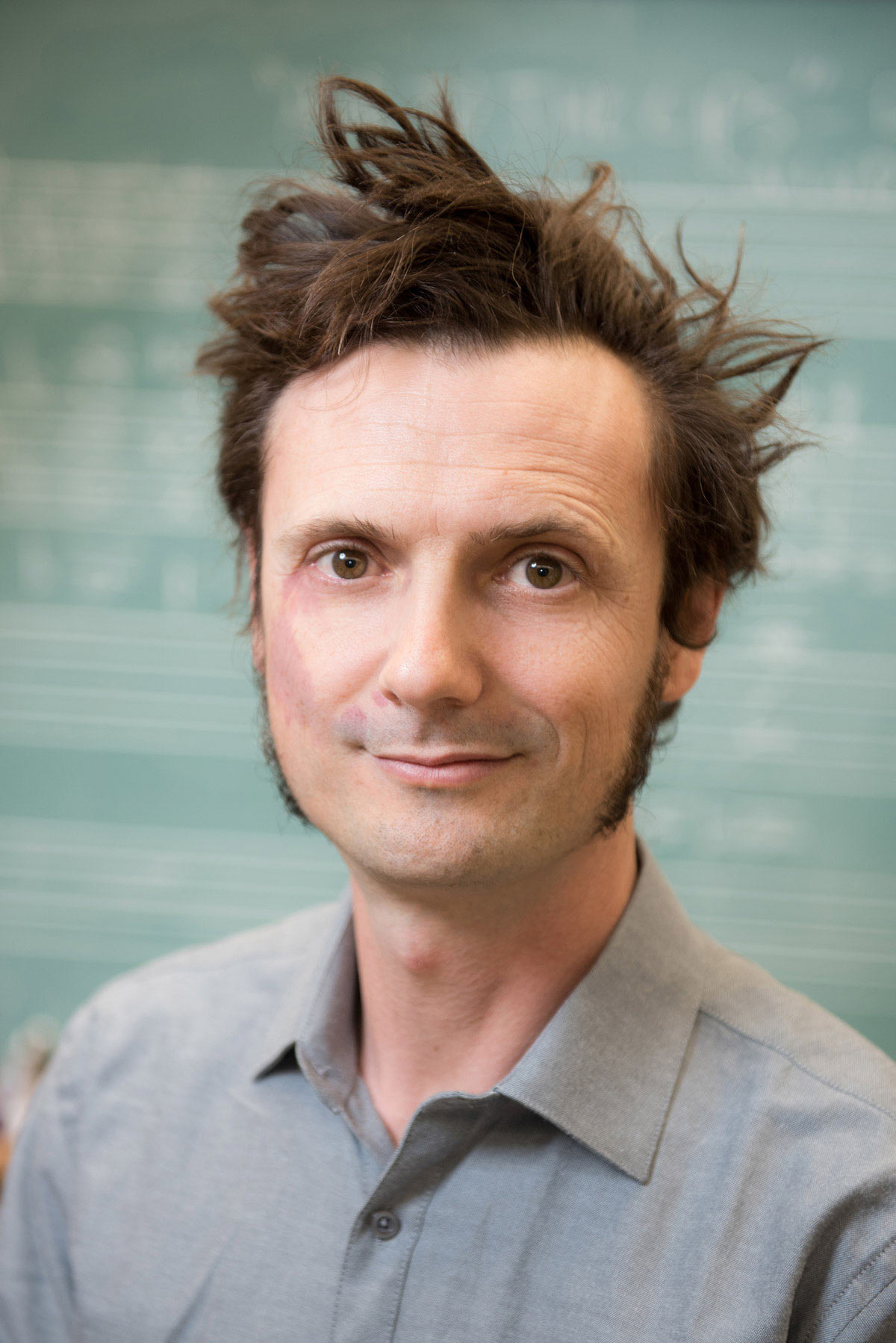

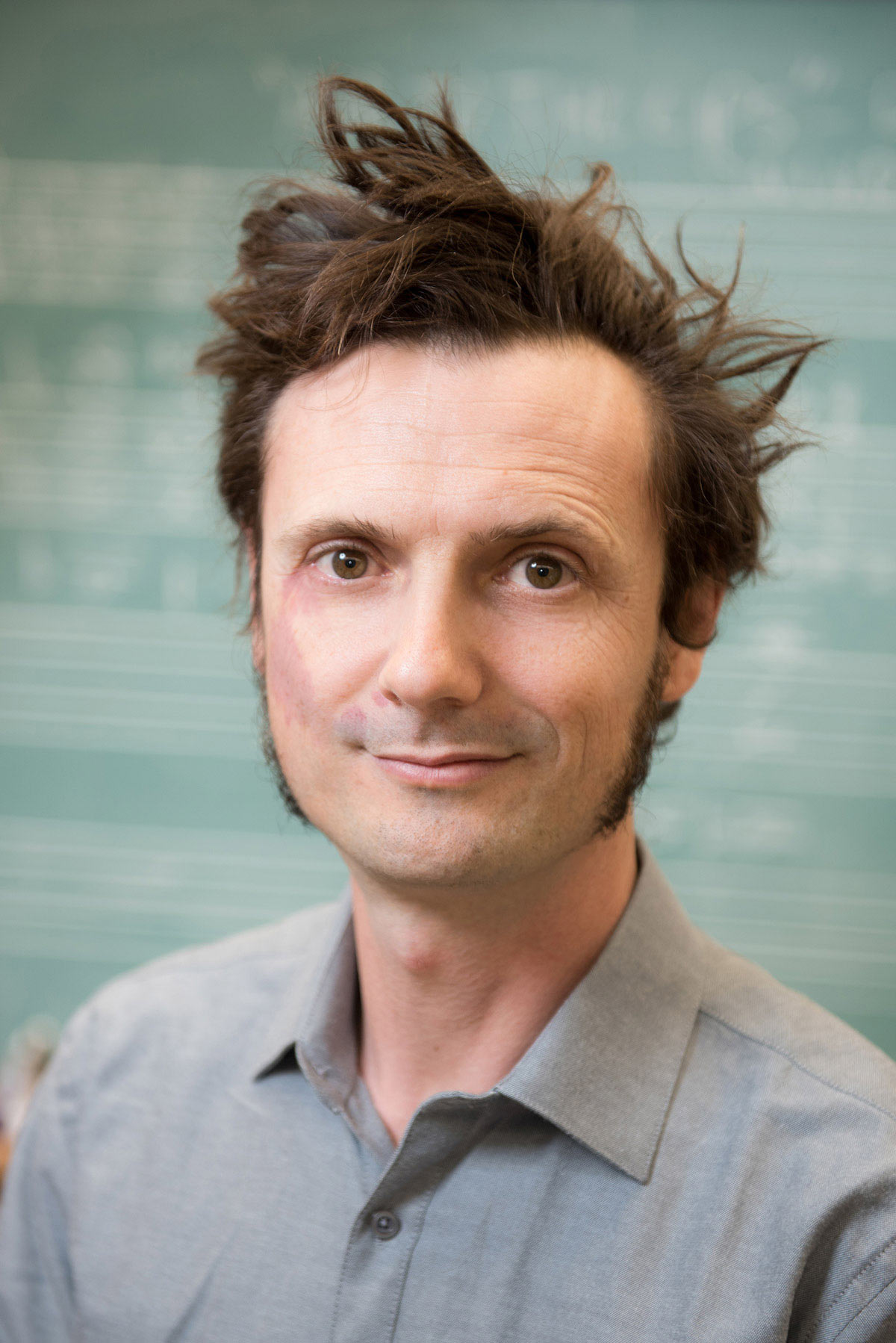

Dylan Champagne, a senior studying composition at the University of Idaho, and some friends were kicking around ideas and thought it would be fun to watch a silent movie accompanied by a real-life orchestra.

It was a “hare-brained idea,” but Champagne wanted to see if it could be pulled off. So he grabbed a copy of Lon Chaney’s 1925 horror spectacle “The Phantom of the Opera” and started writing the music.

“I composed some rough sketches and it kind of snowballed from there,” said Champagne, who will graduate this spring with a bachelor’s degree from the College of Letters, Arts and Social Sciences (CLASS).

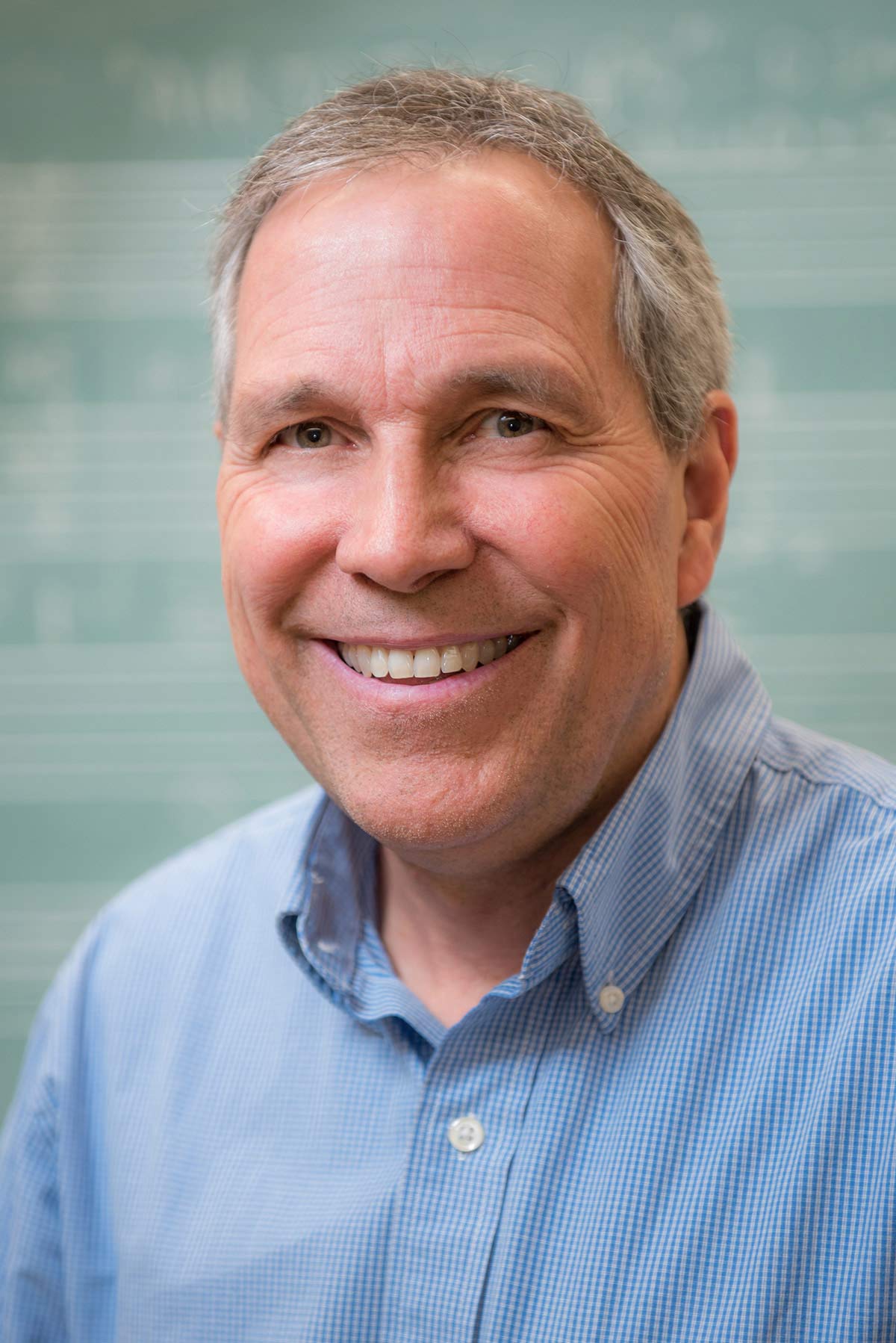

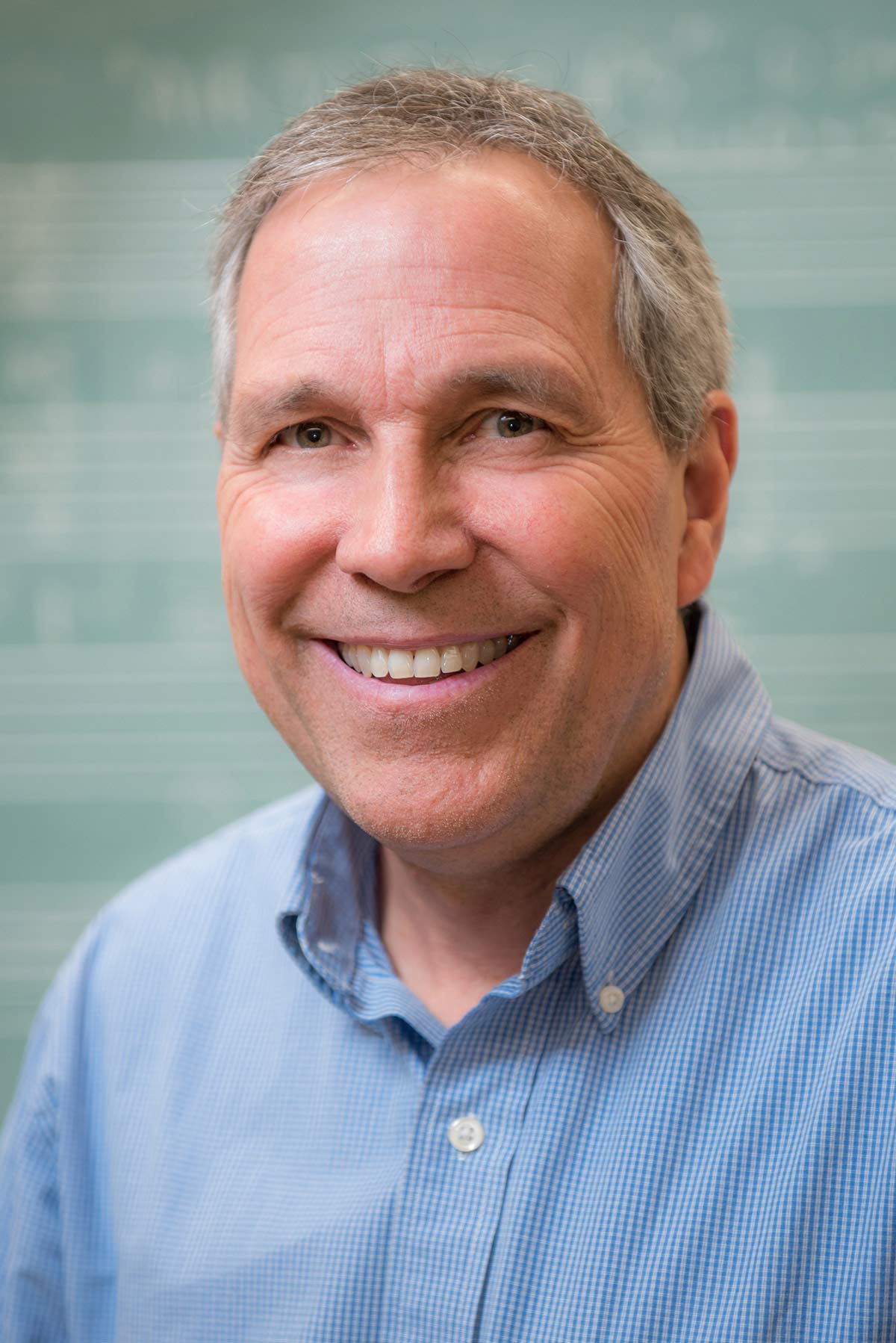

More than a year later, Champagne and Lionel Hampton School of Music Professor Alan Gemberling are readying the project for its second performance. Gemberling will conduct an eight-piece chamber orchestra at 7 p.m. April 13 as it performs Champagne’s score in front of an audience at the Garland Theater in Spokane.

It’s the second such rendition of the score, which Champagne has refined and tinkered with since an initial staging last year at the Kenworthy Performing Arts Centre in Moscow. He has since received a $1,500 undergraduate collaborative research key grant from CLASS to rent the Spokane theater, make copies of the score and publicize the venture.

The musicians, which include members of the Palouse String Quartet, are performing the project as an experiential endeavor. Many people have not seen the movies of Hollywood’s silent era, let alone alongside live music.

The score is different than any previous composition embedded in the film. Champagne purposely didn’t listen to any of the several scores that exist for the film until after writing his work so he could take on the project with an independent mind.

Without the use of sound, silent films relied heavily on a visually rich world that was created by the film’s producers. Movie makers didn’t necessarily have a knack for cinematography, Champagne said, “so they set up a camera and did their thing.”

“It’s a huge world,” he said of silent movies. “I feel like I’ve only scratched the surface.”

Except for a few scenes in which the film excerpts the opera “Faust” and a melody, the score and its measures of “creepy clarinet” and “angry cello” is entirely from Champagne’s mind. His eight-piece ensemble includes a flute, clarinet, violin, bass and percussion, along with members of the Palouse String Quartet bowing on the viola, cello and violin.

Everyone has cued parts, and Champagne said he doesn’t let any single musician get more than 12 measures of rest before they get a cue to let them know where they are in the score.

Gemberling has high praise for his pupil. He said Champagne did a nice job of inserting visual cues in the score so he and the musicians have an idea of what is happening in the movie and where the conductor needs to be in the composition.

“It was so much fun,” Champagne said of writing the score and seeing it come to life for an audience. “Despite the number of hours I put into this, it rarely felt like work.”

Even so, Champagne and Gemberling each throw around phrases like “huge undertaking” and “exhausting” when they describe the project.

They aren’t kidding.

The 107-minute movie is split into two acts, but the individual parts the musicians read collectively add up to about 500 pages of sheet music. Each page must match the action on screen to a T.

“It’s absolutely the most challenging piece I’ve ever had to conduct,” Gemberling said. The endurance level that must be met for 45 minutes during each act of the film is almost double most pieces he’s helmed over the course of his career. “Other pieces of music to a certain extent are up to my interpretation and this, I felt like I had to let the film interpret the music. The music had to enhance the film.”

And unlike a stage play or a musical performance where the conductor can speed up or slow down the show based on the speed of the actors or of certain instruments, Gemberling said everything that accompanies the movie has to be identical each time out.

“The film is what it is,” Gemberling said. “It’s going to be exactly the same every time. So there is precision to it.”

The movie doesn’t include an intermission, but Champagne inserted one to give the musicians a short break between acts.

For Champagne, the performance is a payoff after more than a year of effort. He’s been workshopping the score ever since the first performance at the Kenworthy last year, he said, deleting measures and fixing articulations in his composition.

The workflow of composing for an existing production is similar to animation, work Champagne regularly performed while employed as a motion graphics artist in the San Francisco Bay area before coming to UI.

But even after writing and rewriting the score, Champagne said he’s only seen the film in its entirety a handful of times. That doesn’t include the countless viewings he’s had of every scene to get his composition just right.

“I still love it,” he said. “I can count on one hand how many times I’ve seen it from beginning to end.”

While it may have started out on a lark, silent movies have become serious business for Champagne and Gemberling. They’re already planning their next outing to accompany the silver screen in fall 2017.

“We’re doing another one at the Kenworthy in September,” Champagne said. “’Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.’ I like silent movies.”

Article by Brad Gary, University Communications & Marketing